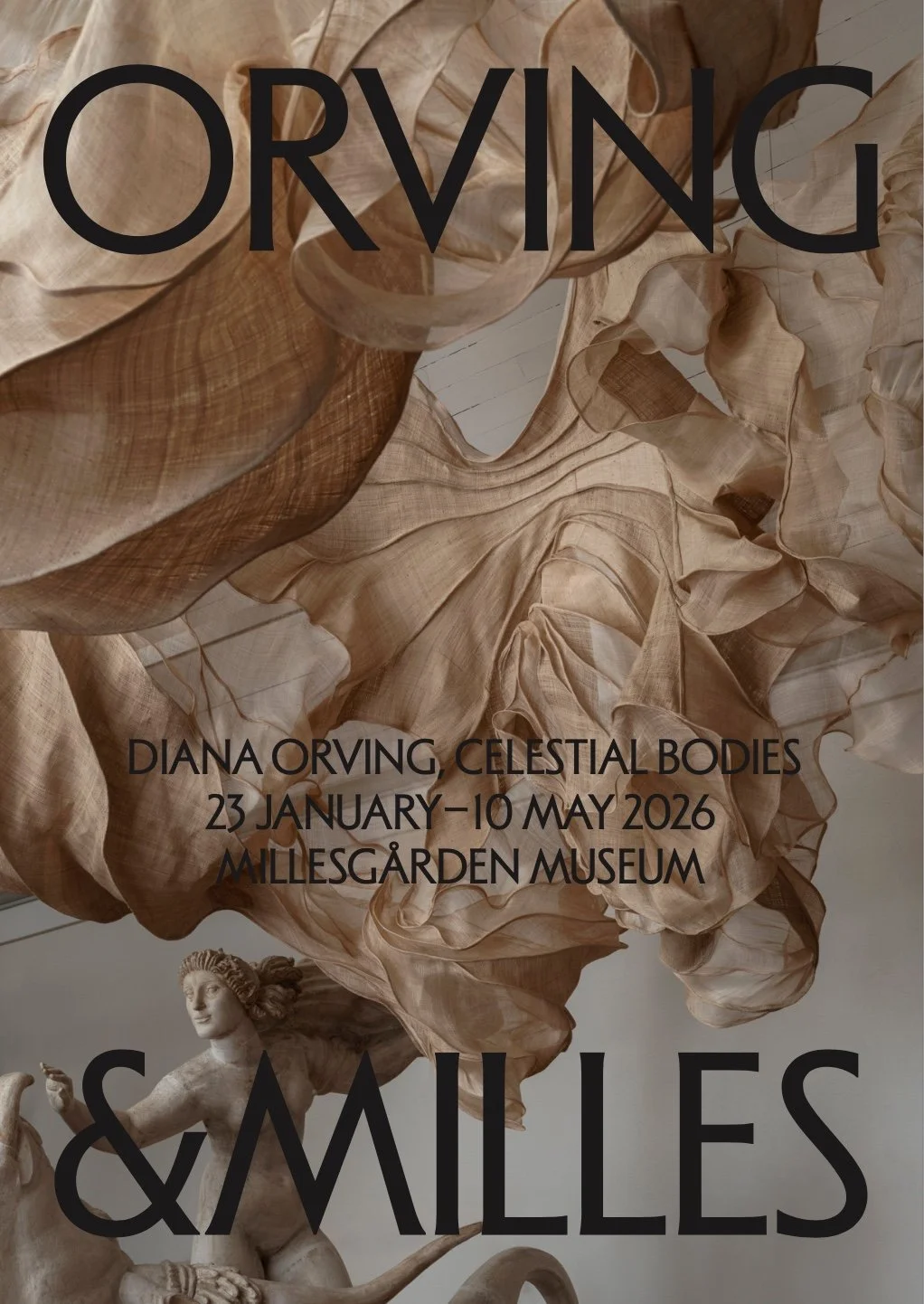

HIMLAKROPPAR ( CELESTIAL BODIES)

DIANA ORVING &MILLES

Millesgården Museum, Stockholm, Sweden

January 23 - May 10, 2026

https://www.millesgarden.se/en/exhibitions/milles-1

Introduction

In the exhibition Celestial Bodies, Diana Orving’s textile sculptures fill the Artist’s Home, where they come into contact with Carl Milles’s world of mythology and astronomy. In the Large Studio – where Milles’s figures seem to hover between heaven and earth – a dialogue opens up between different materials and expressions, between past and present.

Just as Milles created works that reach for the sky, Orving’s sculptures occupy the room with a buoyancy that seems to defy gravity. Orving sews textile layers of silk, linen and abaca – a fibre from a banana plant – into organic shapes that evoke clouds, wind and plants in motion – or birds in flight.

The title Celestial Bodies refers to Milles’s lifelong fascination with winged creatures in myth and nature, and to the idea of art that strives upwards, toward the sky and heavens. Here, two artistic practices meet in the cosmic and the human – celestial bodies in transformation and metamorphosis, serving both as stars and as symbols of humanity’s desire to transcend boundaries.

Thirteen ways of looking at Diana Orving and her wings (and a blackbird) by Sara Stridsberg

I. My latest novel Farewell to Panic Beach begins at Milles playing bears, right at the entrance to Berzelii Park. The small granite bears tear at each other’s throats and rake hard claws towards one another’s eyes, yet they look so happy as they tumble about – like a single celestial body among celestial bodies.

II. I found myself thinking of those bear cubs when I visited her studio recently. The artist stood beside her blackbird, looking like a bird herself. She wore a black fur vest that resembled wings, her body small and bird-like as she moved about in her floating worlds of membranes and clouds, which were momentarily piled in drifts on the floor, waiting to take flight again.

III. The blackbird was silent where it stood, in its own world. The blackbird is the angel of reality, writes the poet Wallace Stevens.

IV. If Michelangelo saw a complete sculpture within a marble block, then in Orving’s work we get a glimpse of worlds that once existed but have since been lost and possibly might re-emerge. I think of Camille Claudel’s sculpture The Waltz. Below the waist, the man and woman are swept up in the mad waltz of love, merging into a single lump of clay. As they dance, they revert to stardust and earth. Similarly, Diana Orving captures both the movement, its cessation and a possible continuation.

V. That is probably why everything in Orving’s work hovers, rising upwards as it defies gravity, like a dream of suspend- ing death. Everything except the blackbird, which is the only one here that ought to be flying.

VI. Perhaps we find ourselves immersed within the mem- branes of the body, or far out in space among nebulae and stellar reefs. A world of umbilical cord spheres and solitary luminous shells.

VII. Nevertheless, her celestial bodies arouse a singular thirst, a hunger – desire, one might call it. Not a desire to possess anything, but rather to race through the halls of Millesgården and eat it all up, like the witch Pomperipossa herself, munching on clouds and seashells and spirals and light.

VIII. It’s as if the artist is saying: It’s not dangerous. Don’t be afraid.

IX. At first she was a fashion designer. The feeling of wings and floating was present even then. Was that why everyone coveted her dresses and coats – because they all wanted to fly away? Like the lady, the man, and the ape, who during the final costume change transforms into a bird that takes off and flies away in Marie-Louise Ekman’s work Striptease.

X. Play, currents, infinity.

XI. Birds of light flying against glass, but without being crushed.

XII. It is evening now, but this blackbird does not fly. It stands alone in a corner. It seems to be the only thing here that must submit to gravity. Clumsy, blind and tired. With- out sky, without eternity. Surrounded by dreams, clouds and tattered thoughts, by all this Orvingian longing.

XIII. Please, please call me when you reach heaven.

Wallace Stevens wrote the poem Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird. I was reminded of it when I encountered the blackbird in Diana Orving’s studio.

/ Sara Stridsberg

Biography

Diana Orving (b. 1985) is a Swedish artist based in Stockholm. She primarily works with textile sculpture and painting, exploring themes of memory, origin, and the subconscious, where the tactile meets the visual and the body’s relationship to space is central. While sculpture is often understood through its surface, Orving turns her attention inward – toward structure, flow, and movement, treating form almost as a living organism. Through seams that resemble veins or branching systems, she creates immersive environments that invite both physical and sensorial presence.

Her work has been exhibited internationally, including in New York, Milan, the Netherlands and at Art Brussels, as well as in Swedish institutions and art galleries around the country.

Exhibition concept

&Milles is a new exhibition series that places the total work of art Millesgården – bequeathed to the Swedish people in 1936 – in active dialogue with the present. Contemporary artists are invited to create site-specific installations in relation to the unique environment, where the Artist’s Home and the surrounding sculpture park can also serve as sources of inspiration. Millesgården’s ambition and intention is to remain a place for artistic exploration and innovation.

Curator: Evelina Berglund, Curator of Collections & Archive. Production: Bronwyn Griffith, Head of Exhibitions. Graphic Design: The Studio. Installation: Hangmen Studios. Photo: Erik Lefvander. Translation: Eva Tofvesson Redz.